The Pacific nation of Tuvalu is replicating itself in the metaverse in an innovative bid to safeguard its culture and sovereignty in the event of territory loss and displacement due to climate change.

The low-lying islands could become uninhabitable by 02100 due to rising sea levels, according to a study cited by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. By migrating governance and administrative systems to the metaverse, Tuvalu hopes to continue functioning as a state, regardless of where its government or people are located in the world. This works alongside Tuvalu’s current efforts to legislate permanent statehood and maritime boundaries, which climate change threatens under current international law.

“Our hope is that we have a digital nation that exists alongside our physical territory, but in the event that we lose our physical territory, we will have a digital nation that is functioning well, and is recognized by the world as the representative of Tuvalu,” Simon Kofe, the leader of the project and Minister for Justice, Communication, and Foreign Affairs of Tuvalu, told Long Now.

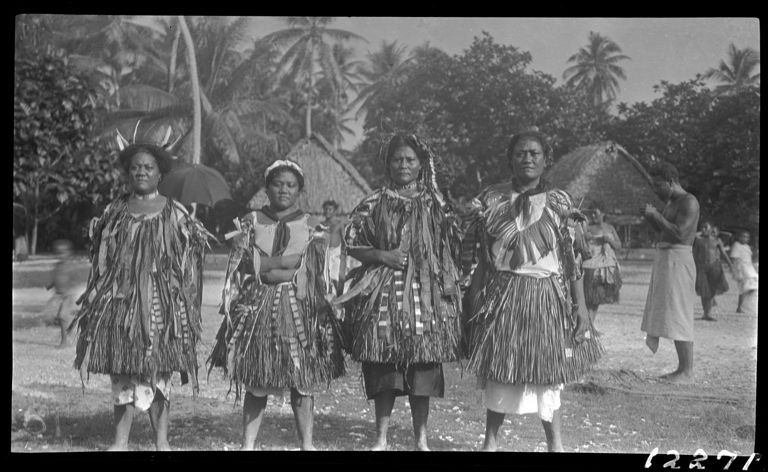

Tuvalu’s physical landscapes will be preserved through virtual twins, beginning with the small islet of Te Afualiku, one of the first places in Tuvalu likely to be submerged due to rising sea levels. In efforts to preserve cultural heritage, stories, traditional songs, historical documents and recorded cultural practices will be cataloged and digitized.

“We want to be able to take a snapshot of what culture is today, and allow my children and grandchildren to have that same experience wherever they are in the world,” Kofe said.

“So even if the physical territory is lost, we would never lose the knowledge, culture, and way of life that Tuvaluans have experienced and lived for many centuries.”

[Watch: Wade Davis’ 02010 Long Now Talk, “The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World,” which explores in part how Polynesian navigators mastered the Pacific Ocean without writing or chronometers.]

Guy Jackson, a human geographer and researcher specializing in climate-driven non-economic loss and damage, says that the biggest risks climate change poses to cultural heritage in Tuvalu are territory loss and changes in seasonality.

Small island nations are deeply connected to their sense of place, and as seasonality changes due to climate impacts, knowledge of the availability of species, foods and migratory patterns change, which Jackson says leads to a massive loss and sense of grief.

He says that while a preservation project such as this cannot arrest the mental health impacts of losing one’s territory, for those displaced, knowing that there is a record of land, important sites, and stories, could come with positive benefits.

“I imagine within the metaverse there will be stories linked to particular places so you can imagine as a young person, being displaced from your home due to climate change, it would be a way to stay grounded in your particular culture while obviously, things will still change. Having this as a place that could probably evolve and grow will give people a sense of continuity, despite all of the changes and uncertainties,” Jackson said.

“For diaspora communities, and with Tuvalu having a lot of people living outside of the country, even for people like that who aren’t technically displaced by climate change, having a record like this will be a great place for people to go to and consider and enjoy their heritage, and then use that to help the next generations that might not have access to that land.”

The use of digital twins for cultural heritage has predominantly focused on capturing the visual appearance of objects, collections, and sites, with a suite of historical buildings and museums becoming digitized.

Horizon 2020, the European Union’s research and innovation program, cited a need for a more holistic approach to cultural heritage digitization, expanding beyond the recreation of visual and structural information to capture stories and experiences, and their broader ‘cultural and socio-historical context’.

In this way, Jackson sees Tuvalu as a forerunner, and believes that their approach will spark other countries to use similar methods to preserve their ‘important landscapes, memories, and stories.’

Kofe says that beyond its future applications, having a virtual copy of Tuvalu has immediate benefits that will help the government be more efficient for its people.

“Anything that you can think of in terms of data that is collected in Tuvalu, it can all be uploaded onto the digital twin,” he said. “We can track the impacts of climate change on the islands, entering data that we’ve collected for many decades, and make projections into the future. With a lot of commercial fishing activity in Tuvalu, you can have real-time data showing the vessels, the fishing locations, the amount of fish, and the species that are being caught.”

In the event that Tuvalu loses their islands, having a virtual copy could also assist them in reconstructing their land.

While unique in its scope and connection to climate mobility, Tuvalu is not the first nation to commence a digitization project within the metaverse. Barbados is building a virtual embassy with the development of infrastructure to provide services such as ‘e-visas’ and a ‘teleporter’ that will allow users to travel through all meta worlds. The South Korean capital of Seoul aims to have a metaverse environment for all of its administrative services by 02026.

James Cooper, an international law expert and Director of International Legal Studies at California Western School of Law in San Diego, says that these moves within the metaverse raise issues of jurisdiction, liability, sovereign immunity, and human rights.

He believes these should be answered and regulated before technology and events outpace lawyers’ ability to do so.

“Whose laws apply?” Cooper asks. “How do you address the rights of a citizen from another country who might be in the metaverse on your government services platform or space within the metaverse?”

“What do you do for people who may be hearing or sight impaired and not able to fully access the metaverse or have the financial means or the connectivity? Are they being placed in a compromised role or limited in the same access that they would otherwise get?”

Cooper says that Tuvalu’s small population of 11,000 people will give them an advantage in addressing these issues compared to a larger nation.

As the project enters its beginning stages, Kofe stresses that preparing for a worst-case scenario by no means indicates a reduction in the nation’s climate advocacy or fight for a just future. He says the government is and will continue to work to protect its islands by building sea walls, reclaiming land, raising the islands in different parts, and calling for international mitigation measures.

“You could say the project is a Plan B, because the ordinary Tuvaluan, if you talk to them on the streets, none of them want to actually leave the islands,” Kofe said. “My hope is that there’s a strong message that people can see when we are doing this. I’d like them to imagine if they had to plan for relocation because of climate change.”

According to Kausea Natano, the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, Pacific Island nations contribute less than 0.03% of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Kofe says that the primary solution to climate change is for bigger countries to reduce their emissions, and he hopes that this project will inspire the public to rise up and put pressure on their leaders to do exactly that. In his COP27 address he emphasized that while Tuvalu could be the first country in the world to exist solely in the metaverse, if global warming continues unchecked it won’t be the last.